Thursday May 7, 2015

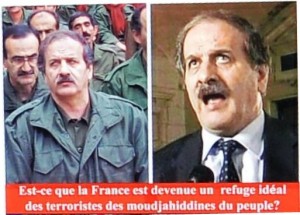

Mehdi Abrishamch a high ranking member of a Terrorist Cult Group called PMOI was summoned for a court hearing by the French Judiciary and questioned with regards to money laundering.

Mehdi Abrishamch is the ex-husband of Maryam Rajavi, the Cult’s Leader’s (Mr. Masoud Rajavi) wife now. Maryam Rajavi is based in Auvers Sur Oise North of Paris.

The Cult force divorced the women from their husbands which were all later married to the Cult Leader Masoud Rajavi.

In 2003, Maryam Rajavi’s office in Auvers Sur Oise North of Paris was raided by French police. She was arrested together with 160 members of the Cult and the assets of the NCRI together with millions of Dollars of cash in the Maryam Rajavi’s safe were frozen by the French government.

Ex-members of the Cults gathered outside the court in support of the court. They demanded the release of the members still trapped in the Cults Iraq Liberty Camp.

The New York Times then published an article by By ELIZABETH RUBIN titled “The Cult of Rajavi” which can be reached at the following link: http://www.nytimes.com/2003/07/13/magazine/13MUJAHADEEN.html

The Cult of Rajavi

By ELIZABETH RUBIN

Published: July 13, 2003

For more than 30 years, the Mujahedeen Khalq, or People’s Mujahedeen, has survived and operated on the margins of history and the slivers of land that Saddam Hussein and French governments have proffered it. During the 1970’s, while it was still an underground Iranian political movement, you could encounter some of its members on the streets of New York, waving pictures of torture victims of the shah’s regime. In the 80’s and 90’s, after its leaders fled Iran, you could see them raising money and petitioning on university campuses around the United States, pumping photographs in the air of women mangled and tortured by the Islamic regime in Tehran. By then, they were also showing off other photographs, photographs that were in some ways more attention-grabbing: Iranian women in military uniforms who brandished guns, drove tanks and were ready to overthrow the Iranian government. Led by a charismatic husband-and-wife duo, Maryam and Massoud Rajavi, the Mujahedeen had transformed itself into the only army in the world with a commander corps composed mostly of women.

Until the United States invaded Iraq in March, the Mujahedeen survived for two decades under the patronage of Saddam Hussein. He gave the group money, weapons, jeeps and military bases along the Iran-Iraq border — a convenient launching ground for its attacks against Iranian government figures. When U.S. forces toppled Saddam’s regime, they were not sure how to handle the army of some 5,000 Mujahedeen fighters, many of them female and all of them fanatically loyal to the Rajavis. The U.S soldiers’ confusion reflected confusion back home. The Mujahedeen has a sophisticated lobbying apparatus, and it has exploited the notion of female soldiers fighting the Islamic clerical rulers in Tehran to garner the support of dozens in Congress. But the group is also on the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations, placed there in 1997 as a goodwill gesture toward Iran’s newly elected reform-minded president, Mohammad Khatami.

With the fall of Saddam and with a wave of antigovernment demonstrations across Iran last month, the Mujahedeen suddenly found itself thrown into the middle of Washington’s foreign-policy battles over what to do about Iran. And now its fate hangs precariously between extinction and resurrection. A number of Pentagon hawks and policy makers are advocating that the Mujahedeen be removed from the terrorist list and recycled for future use against Iran. But the French have also stepped into the Persian fray on the side of the Iranian government — who consider the Rajavis and their army a mortal enemy. In the early-morning hours of June 17, some 1,300 French police officers descended upon the town of Auvers-sur-Oise, where the Mujahedeen established its political headquarters. After offering the Iranian exiles sanctuary on and off for two decades and providing police protection to Maryam Rajavi, the French mysteriously arrested Rajavi along with 160 of her followers, claiming that the group was planning to move its military base to France and launch terrorist attacks on Iranian targets in Europe. Immediately, zealous Mujahedeen members in Paris, London and Rome staged hunger strikes, demanding the release of Maryam, and several set themselves ablaze.

In Washington, Senator Sam Brownback, Republican of Kansas and chairman of the Foreign Relations subcommittee on South Asia, accused the French of doing the Iranian government’s dirty work. Along with other members of Congress, Brownback wrote a letter of protest to President Jacques Chirac, while longtime Mujahedeen champions like Sheila Jackson-Lee, Democrat of Texas, expressed their distress over Maryam’s arrest. But few, if any, of these supporters have visited the Mujahedeen’s desert encampments in Iraq and know how truly bizarre this revolutionary group is.

ecently, I went to visit Camp Ashraf, the main Mujahedeen base, which lies some 65 miles north of Baghdad in Diala province, near the Iranian border. Ashraf is 14 square miles of ungenerous desert surrounded by aprons of barbed wire, gun towers and guards in trough-like bunkers, shaded by camouflage netting and dehydrated palm trees, their trunks thickened by dust. As you pass the checkpoints and dragons’-teeth tire crunchers into the tidy military town, you feel you’ve entered a fictional world of female worker bees. Of course, there are men around; about 50 percent of the soldiers are male. But everywhere I turned, I saw women dressed in khaki uniforms and mud-colored head scarves, driving back and forth along the avenues in white pickups or army-green trucks, staring ahead, slightly dazed, or walking purposefully, a slight march to their gaits as at a factory in Maoist China.

Pari Bahshai, a stocky Iranian woman in her mid-40’s and the military commander of Ashraf, was my tour guide for the day. We drove through the grounds in her white Land Cruiser out to a dry, burning plain where dozens of young women were buried in the mouths of their tanks — adjusting, winching, tinkering with the circuits and engines that keep their fighting machines alive. There were neat rows of Brazilian Cascavel tanks, Russian BMP armored vehicles and British Chieftains, most of them captured from Iran at the end of the Iran-Iraq war.