An Islamic State flag hangs amid electric wires over a street in Ain al-Hilweh, a Palestinian refugee camp near the port-city of Sidon, in southern Lebanon, on January 19, 2016. ALI HASHISHO/REUTERS

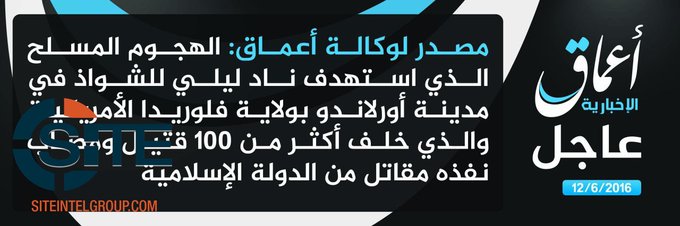

WHEN FACED WITH acts of unfathomable cruelty, humans instinctually seek simple narratives that can help us cope with the existence of such evil. In the immediate aftermath of the atrocity in Orlando, much of our national conversation has focused on whether the killer, Omar Mateen, was an agent of the so-called Islamic State, or ISIS. A few bits of evidence have emerged that could be construed as supporting that theory: The Islamic State’s faux news agency, Amaq, identified Mateen as a “fighter” for the organization, while Mateen himself reportedly pledged fealty to the group in a 911 call just moments before the attack.

A casual observer might therefore conclude that the massacre was devised in Syria or Iraq, and that Mateen was in contact with Islamic State officials regarding his preparations—much like the young men who sowed horror in Paris last November. That is a story that, albeit grim, at least provides some solace: It implies that there is a linear network between the Islamic State and its American sympathizers that can be identified, and destroyed.

But as of now there is no evidence ISIS knew of the shooter or the attack beforehand. And the history of ISIS-related attacks in the US suggests that much about the Orlando tragedy will always perplex, no matter how much we delve into Mateen’s past or his hard drives. That is because when Americans perpetrate violence in the name of the Islamic State, they tend not to be strict adherents of the organization’s ideology, but rather disturbed individuals who hope to layer a political façade atop their personal grievances—grievances sometimes known only to themselves.

These people elect to wrap themselves in the Islamic State’s brand because of its unparalleled notoriety, an image that the group has cultivated through a sophisticated propaganda campaign that has taken advantage of social media’s power and pervasiveness. As I wrote earlier this year, the Islamic State’s media operation is focused not just on luring recruits to emigrate to the “caliphate,” but also on tapping into the psyches of twisted souls searching for meaning:

The most significant way in which the Islamic State has exhibited its media savviness has been through its embrace of openness. Unlike al Qaeda, which has generally been methodical about organizing and controlling its terror cells, the more opportunistic Islamic State is content to crowdsource its social media activity—and its violence—out to individuals with whom it has no concrete ties. And the organization does not make this happen in the shadows; it does so openly in the West’s most beloved precincts of the Internet, co-opting the digital services that have become woven into our daily lives. As a result, the Islamic State’s brand has permeated our cultural atmosphere to an outsize degree.

This has allowed the Islamic State to rouse followers that al Qaeda never was able to reach. Its brand has become so ubiquitous, in fact, that it has transformed into something akin to an open source operating system for the desperate and deluded—a vague ideological platform upon which people can construct elaborate personal narratives of persecution or rage. Some individuals become so engrossed in those narratives that they scheme to kill in the Islamic State’s name, in the belief that doing so will help them right their troubled lives. Here in the US, the group’s message has found a foothold among people who map their own idiosyncratic struggles and grievances, real or imagined, onto the Islamic State ideology. These half-cocked jihadists, while rare, come from all walks of American life, creating a new kind of domestic threat—one that is small in scale but fiendishly difficult to counter.

As I also mentioned in that piece, these lone-wolf actors—terrorists like Mateen—have a historical precedent: The American airplane hijackers of the late 1960s and early 1970s. It’s easy to forget, but “skyjackers” commandeered nearly 160 commercial planes before metal detectors and X-ray machines became ubiquitous in airports. Many of these hijackers claimed to be acting on behalf of militant groups when they seized flights and demanded passage to Cuba or seven-figure ransoms.

Yet few had bona fide ties to those groups; they were, instead, people whose worldviews had been warped by personal crises, from run-ins with the law to romantic disappointments. In their darkest hours, they encountered play-by-play media coverage of other hijackings, which often dominated the evening news, and glimpsed a dramatic solution to their problems—a way to indulge their narcissism by becoming what America professed to fear most.

Once the airlines’ resistance to tighter security melted away, the hijacking epidemic was rather easy to curtail. That will not be the case with the open source system that the Islamic State has created, which will be studied and replicated by the organization’s inevitable successors. Just as the Islamic State was at first just a small ideological spore that drifted away from al-Qaeda, other movements will branch off from the Islamic State as its power diminishes due to military onslaughts. And those movements will be well aware that a relative pittance spent on media production and dissemination can incite attacks that cause its enemies incalculable sorrow.

If the past is any guide, the Islamic State’s various media offices will seek to capitalize on the Orlando attack, even if the organization had no direct involvement in its conception or execution. Like Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik, the married couple who murdered 14 people at a holiday party in San Bernardino, California last year, Mateen will be lionized for fulfilling his alleged obligation to the caliphate.

Such disgusting rhetoric is designed to elicit a very specific response from the West: The Islamic State wants us to feel compelled to abandon our core values in the name of security. The jihadist theorist Abu Bakr Naji referred to this strategy as “cultural annihilation”—in essence, using terror to egg an enemy into myopically tearing apart its own social fabric.

The Islamic State wants us to question our commitment to pluralism, to make us view it as a vulnerability rather than a strength. Its greatest dream is that we turn against Muslims and Islam right now. In being vigilant about avoiding that well-laid trap, we can demonstrate why our vision for society is the one that offers the world a true way forward.

“I think ultimately, the strength of our society is going to emerge in how we deal with this,” says Brian Michael Jenkins, a terrorism expert at the Rand Corporation. “Our success is not going to come from how many concrete barriers we can plant in front of buildings; it’s going to be come from how we’re able to let our fundamental values prevail.” Those values—of civility, inclusiveness, and love—are what we must emphasize in the narratives we begin to construct in these difficult days of mourning.